Experience Heaven on Earth

A Guide to Understanding and Participating in the Byzantine Divine Liturgy

THE DIVINE LITURGY is the Byzantine name for the Eucharistic Liturgy or the Mass.

ICONS, often called “windows into heaven,” are the most ancient and sophisticated form of Christian art. Icons are important to the Byzantine Divine Liturgy because they:

• make clear the message of the Gospel of the Incarnation.

• make visible the invisible presence of angels and saints.

• make known the fullness of the future Kingdom to which we must strive.

• emphasize the Saint(s) we are commemorating or the Mystery of Faith we are celebrating.

• remind us that we are each called to be the Icon, that is, a sinless Image of the Divine.

The two primary Icons of Mary and Jesus on either side of the altar represent the two comings of Christ. The Icon of Mary holding the Christ child represents the first coming of Christ in the flesh; on the other hand, the Icon of the adult Christ represents the second coming of Christ in glory. Between these two “comings” we have intimacy with Christ through the celebration of the Lord’s Mystical Banquet—the Most Holy Eucharist.

METANIA or metanoia, from the Greek, “to turn to God,” is a pious reverence that involves a deep bow and a simultaneous sign of the cross done repeatedly throughout the Liturgy.

UPON ENTERING THE CHURCH, if there is holy water, bless yourself as usual. Instead of genuflecting, proceed forward to the tetrapod or Icon stand, which is set up front in the middle aisle, make two profound metanias to the Divine Presence, reverence the Icon with a kiss, then make another metania before departing. Light a candle if candles are available, pray, then return to your seat and join in the pre-liturgical prayers once they begin.

FACING EAST — As early as 150 AD and certainly since the time of the Holy Council of Nicea in 325 AD, ideally, every Church, every altar, every congregation, and every celebrant was encouraged to face east toward the rising sun representing the risen Christ. Whether or not the building actually faces east, the priest with the congregation face the invisible presence of Christ who is the real presider of each Eucharist.

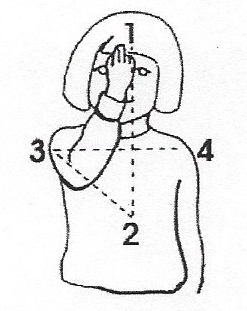

THE SIGN OF THE CROSS is made repeatedly at the mention of the Trinity or any other prayer done in a sequence of three. The sign of the cross is properly made by joining the thumb, index, and fore fingers together to represent the Holy Trinity of God.

Leaving the remaining fingers to point back at the heart, representing the divine and human natures of Christ through which God joins himself to us in the Incarnation. The signing is from the right shoulder to the left, as was the ancient practice of ALL Catholic Churches up to the 11th century.

STANDING is a sign of the Resurrection and is the primary posture at Eastern Liturgies. Though the faithful may kneel from the singing of the Holy, Holy, Holy to after the consecration, most worshipers have developed the discipline of standing upright. While no disrespect is intended to the western church’s practice of kneeling, the Byzantine Rite follows the practice of the early church where believers (many of whom were slaves) celebrated their spiritual freedom in Christ by standing.

INCENSE, used throughout the Liturgy, represents:

• our prayers rising before God in heaven

• the diffuse presence of the Holy Spirit

• the cloud of revelation

• the sweet offering of sacrifice

THEOTOKOS is Greek for “she who bore God in her womb.” The Latin version being Mater Dei or “Mother of God.” Both terms come from the council of Ephesus in 431 AD where the Church proclaimed the “orthodox” idea that Christ is ONE person with two natures (divine and human), and condemned Nestorianism which said Christ was two persons with two natures. By declaring Mary to be the Theotokos, the Church protected the divinity of Christ and the doctrine of redemption. That is, God became human so we could become divine. You will hear this title for the Blessed Virgin throughout the Liturgical action.